SPELLCAST:

Chapter One (excerpt)

Some Enchanted Evening

As soon as the barn came into view, my heart started racing. And – right on cue – my foot came off the gas pedal. Clearly, my body wanted me to stop, even if my mind was firmly against the idea.

What the hell. It couldn’t hurt to look at the place.

I eased my car down the narrow lane, trying to avoid deep ruts that looked like they had been carved by the Conestoga wagons of Dale’s original settlers. A white farmhouse sprawled atop a hill, overlooking the meadow and barn much the way the house in Psycho looms over the Bates Motel. As I drifted closer, I glimpsed a couple of outbuildings and what might be a small pond. Beyond that stretched the forest primeval.

There were close to two dozen cars in the gravel lot, sporting license plates from all over the Northeast; I even spotted a few from the South.

Even more astonishing were the hopefuls milling around the picnic tables. In addition to the motley crew I’d glimpsed leaving the Chatterbox, I saw a Rocky clone in a muscle shirt, Luca Brasi’s twin brother, two Legally Blonde sorority chicks, a black Rasta dude, a white Rasta wannabe, and an elderly man in a walker serenading a mousy looking woman with a quavering rendition of ‘Some Enchanted Evening.’ A few clutched sheet music, but most were empty-handed and looked as bewildered as I felt.

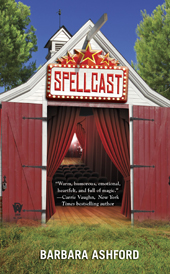

Up close, the theatre was as unimpressive as its prospective actors. The timbers of the barn were more of a sun-bleached gray than white. Ivy crept over its stone foundations to snake up the wood slats. Atop the cupola, a black weathervane in the shape of something vaguely mammalian creaked in the gusting breeze. Shivering, I slipped through the open front door.

Warmth enveloped me. Not merely the physical sensation of walking into a heated building, but something more – like the embrace of an old friend. I shook my head impatiently; no use getting sentimental about the good old days of summer stock.

The small lobby was empty save for an elderly woman sitting in the box office. She looked up from her magazine and examined me over her reading glasses. Her patrician New England face – bone structure to die for – only added to the impression that she was looking down her nose at me. Then she smiled and morphed into the elegant but warm-hearted fairy godmother the Disney animators should have given Cinderella.

“Reinhard will be out in a moment.”

I nodded politely and made a mental note to flee before then. There was still time to look around, though; beyond the two sets of double doors that led to the house, the current victim had just launched into a quavering a cappella version of ‘Born to be Wild.’

A flyer impaled to the wall with a thumbtack advertised next weekend’s Memorial Day parade. Another – bright pink – the “Spring into Summer” sale at Hallee’s. All corsets 25% off.

A poster between the house doors revealed that Janet Mackenzie was the theatre’s producer, while Rowan Mackenzie was its director. Doubtless some chirpy husband and wife team with pretensions of artistic brilliance. They clearly loved musicals because that was all they were doing: Brigadoon, Carousel – hoary chestnuts both – and an original show called The Sea-Wife. Book and lyrics by Rowan Mackenzie. He’d probably bombed in real theatre, but had enough money to start his own to soothe his wounded ego.

God only knew what The Sea-Wife was about; if there were mermaids involved, I was doomed. I’d be perfect for the comic lead in Brigadoon, but I’d always despised Carousel. Maybe because the story hit a little too close to home. Abusive ne’er-do-well woos small town girl, who continues to adore him no matter what kind of crap he pulls. Returns to earth years after his death to square things with his wife and daughter. Misty-eyed finale with everyone singing some plodding anthem of hope and love.

To be fair, Daddy never hit us. And it was only during that last year that he began vanishing for weeks at a time. Then Mom kicked him out and he vanished for good.

A weight descended on my chest. I shrugged it off. I had no intention of wallowing in the past. Or spending the summer singing about bonnie Jean and real nice clambakes. Or auditioning for the Crossroads Theatre.

Belatedly, I realized that ‘Born to be Wild’ had concluded. Before I could beat a hasty retreat, one of the house doors opened. A middle-aged man clutching a clipboard strode towards me.

“Name?” he demanded, pen poised.

“No. Sorry. I’m not—”

“Name.”

“No. See, I’m not here for the auditions.”

“Name!”

The Teutonic bullying brought out my Scotch-Irish temper. “Dorothy Gale. From Kansas.”

His deepening frown chiseled new lines into his forehead. “And I am Glinda, the Good Witch of the North.”

“As if,” a voice proclaimed behind me. “That’s my role.”

I turned to discover a plumpish young man posed dramatically in the entranceway. His pink shirt was roughly the color of Glinda’s gown, but he wore ordinary blue jeans rather than a chiffon skirt and, in lieu of wand, trailed a plum-colored sweater across the floor.

“Reinhard bullies everyone,” he said as he breezed towards us. “But he’s really a pussycat. I’m Hal. Welcome to the Crossroads.”

“Maggie.”

“Ha!” With a triumphant grin, Reinhard scribbled down my name.

“Hal as in Hallee’s?” I ventured.

“Aren’t you the little Miss Marple? Actually, I’m only half of Hallee’s. My other half—”

“Better half,” Reinhard muttered.

Hal stuck out his tongue. “Lee’s closing up shop for me. I have to be here when the cast lists go up. So exciting.”

His radiant smile dimmed as he studied me. In my black tunic and sweatpants, I resembled a lumpish ninja. Doubtless, Hal wished he’d brought along one of those 25% off corsets.

The smile returned with so little effort that it had to be genuine. “You’ll be wonderful. I have a sixth sense about these things. Next week, after you’re settled, you come into the shop. I have a green sarong that’ll look fabulous with that hair.”

Reinhard sighed heavily. “Last name.”

“Graham. I bet you own the Mandarin Chalet.”

“His wife does,” Hal volunteered. “Reinhard is a pediatrician.”

With that wonderful bedside manner, he probably terrified the local children into good health.

“Mei-Yin also does our choreography. I, of course, do costumes. And set design. Lee—”

“She will find all of this out later,” Reinhard interrupted. “Now, she auditions.”

I cast a despairing look at each of my fairy godmothers, but Hal just beamed and the lady in the box office waggled her fingers.

I knew I should turn around and walk out. But something – curiosity? instinct? my father’s musical theatre genes? – impelled me to follow Reinhard into the house.

The doors whispered shut behind us, cutting off the light from the lobby. We stood motionless in the aisle, allowing our eyes to adjust to the dimness.

I’m a sucker for darkened theatres. There’s an air of hushed anticipation, more patient and mysterious than the hush that descends before the curtain rises. As if the theatre holds secrets that it will reveal only to those who will surrender to its magic and allow it to carry them away to another place, another time, another world.

Beneath the odors of dust and old upholstery, I smelled paint and fresh-cut wood, as if the theatre had been erected that morning instead of decades ago. And something more elusive that made me think of warm summer earth and a thick mulch of pine needles.

A shiver crawled up my back. I rubbed my arms, firmly quelling my imagination and the emerging crop of goose bumps.

Mr. ‘Born to be Wild’ must have left via another door for the stage was empty. Thick clouds of dust motes lent a Brigadoony mistiness to the pool of light center stage. The music director’s head peeped over the rim of the orchestra pit, hair gleaming like a newly minted penny. In the center section of the house, I spotted the dark silhouette of the director.

My stomach went into freefall.

“Break a leg, sweetie.”

I started at Hal’s whisper, unaware that he’d slipped in behind us. As Reinhard edged past me, I whispered that I didn’t have any material, that I hadn’t brought a resume or headshot. He ignored my running monologue and marched down the aisle. And once again, I trotted after him like an obedient puppy.

I mounted the five steps to the stage with the alacrity of Marie Antoinette en route to the guillotine. Then I remembered that I was a New Yorker, for God’s sake. And once upon a time, people had paid to see me perform. I straightened my slumping shoulders and strode onto the stage as if I owned it.

A shock of static electricity stopped me in my tracks. And with it, that weird sense of coming home that I had felt when I stepped inside the barn.

Get a grip, Graham.

I took a deep breath, let it out, and walked into the pool of light...